Amazing event - 1500 people from all over Africa, to

discuss, debate, dance, sing and celebrate. I’ve never been to a conference

like it, and believe me I’ve been to a few. I was there to give a keynote,

workshop and take part in the final event of the conference – the Big Debate

but to be honest I gained much more than I gave. To give you some idea of the

humour on hand, during a meal at which I was eating crocodile, zebra, kudu and

springbok, a lad from Uganda asked of Channa (who’s vegetarian), “If you like

animals so much, why are you eating all their food”.

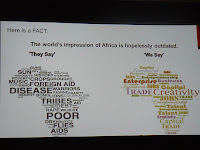

1. New African narrative

Africa

(whatever that is) wants to do things its own way. The people at this event

wanted to change the old pessimistic narrative of poverty, starvation, AIDS,

malaria and dependency, to a new narrative of optimism and self-sufficiency. I

met nothing but friendly, enthusiastic, committed people, who want to do things

the African way.

So what is this African ‘way’? What I think lay at the heart

of the sentiment was the idea that Africa had been subjected to foreign

influences for too long. I constantly heard calls for approaches and contents

to be more relevant, contextualised and in local languages. I gave my own view

in The Big Debate, a wonderfully, raucous event held at the end of the

conference, where I presented evidence that Mitra’s Hole-in-the-Wall projects

ad Negroponte’s Ethiopian adventure were dangerous, unsustainable and at times

downright lies. "Don't let

educational colonialism sneak in... with bucket loads of hardware and content

that is inappropriate for your children." My formidable opponent Adele

said something similar when she urged approaches “By the Africans for the Africans - and we will share best practice with

you when it's done." This debate, on ‘sustainability v innovation’ was

a hoot. Massive audience participation, loads of laughs and although we clearly

won, there was a messy recount and the decision was reversed. When I asked why,

the reply was telling, “Remember Donald,

this is Africa!”

2. Mobiles as lifelines

My keynote talk

was on mobile learning, small beer elsewhere but BIG in Africa. The Nokia 3310

has legendary status in Africa, but Samsung’s the new kid on the block. Africa

loves mobile tech. Calls, text, health, finance – they’ve found a myriad of

ways to use mobiles to enhance their lives. Tariffs are still high but

youngsters would go without food for more airtime. As was explained to me in

the Katatura Township, a mobile for someone in real poverty is far more

important than for someone in a developed country. If you rely on piece-work,

you need to be available to take a call at any time. It’s a way of managing and

transferring what little money you have and receiving remittances from that

relative abroad. It’s a way of switching on your electricity and getting

medical help. It’s a lifeline.

My keynote was all about mobile learning. The very first

piece of technology was invented here in Africa – the stone axe. And for 1.7

million years this was the dominant technology – the first handheld device. But

there’s something odd about stone axes, as many are found in pristine

condition, unused, or as large axes, far too big to be practical. As pieces of

useful technology, they had ‘status’ value. In that sense we have to be careful

about m-learning as they may be seen by youngsters as ‘too cool for school’. My

second piece of advice was to forget ‘courses’. Mobiles are the GPS for

learning, rather than delivering learning itself. Think search, performance

support, informal learning – not courses. Think of contextual learning,

vocational elearning out in the field, reinforcement through spaced practice.

Think different. Also, be careful with video, as few watch video on mobiles,

think audio and text. Media rich is not necessarily mind rich. What I saw in

Africa was the clever use of mobile technology to enhance literacy and

practical learning.

3. Mobiles as motivators for literacy

In my

workshop on ‘Mobiles and literacy’ I was pushing the idea that mobiles had

produced a ‘renaissance of reading and writing’ among the young. It will, I

think, be the single most important factor in increasing literacy on the

planet. Why? Every child is massively motivated to learn to text, post and

message on mobiles. The evidence shows that they become obsessive readers and

writers through mobile devices.

I saw ample

evidence of learning how to read and write through mobiles in what can only be

described as ‘challenging’ conditions. Cornelia Koku Muganda showed us real

evidence for positive results with girls and women in Tanzania, who not only

had to learn to read and write (txt) but who couldn’t afford to make expensive

mistakes such as wrong numbers, wrong codes for electricity switch-on and so

on. Mignon Hardie had a wonderful scheme for young people in the Townships of

South Africa, gaining not only literacy skills but valuable insights into their

own lives through specially written narratives. Ian Mutarami and Mikko Pitkanen

showed how games technology could deliver mobile phonics apps in local

languages.

My own

session focussed on the fact that Africa showed the fastest growth &

massive use of txting. Txting is a significant form of literacy, introduced by youngsters, on their own,

spontaneously, rapidly & without tuition. Oddly, some complain about

poor literacy, but when a technology arrives that provides opportunities to

read and write (constantly) some complain about that! So why the moral panic? Is it a linguistic disaster? No.

Almost all popular beliefs about TXTING are wrong. It’s not new, not for

young only, helps rather than hinders literacy and adds a new dimension to

language use. Language is about being understood and txting has adapted to this

need. Good txters understand that ‘Cnsnnts crry mr infrmtn thn vwls’ and play

with language. Interestingly, women more enthusiastic txters, write longer

txts, more complex txts, use more emoticons, more His & BYEs and more

emotional content (Richard Ling The Sociolinguistics of SMS)

More importantly, txting

benefits literacy as it is a motivating factor in writing (Katz & Aakhus),

requires phonetic knowledge, has links with success in attainment (Wood & Bell), helps one be concise (Fox)

and helps develop social skills (Fox).

4. Hardware

A huge

debate erupted over what devices should be used in learning in Africa. For my

money, the good projects used mobile or notebooks/laptops. Tablets were being

hyped but when I spoke to people they were wary of their lack of flexibility,

low level learning potential, maintenance problems and costs. While they may be

appropriate in some contexts, such as Merryl Ford’s work in rural S Africa and

in early years or primary school, I have serious doubts about their efficacy in

most other contexts. They are impossible to repair, difficult to network and

can severely limit skills development in writing, coding and the use of more

sophisticated software tools.

I was much more impressed

with the laptop projects. Nkubito Manzi Bakuramutsa was an impressive

project manager from Rwanda. He stressed the need for proper infrastructure-

it’s all about wifi, electricity, cabling and sockets. But where he was smart

was in his capacity building of teachers. This is, “fundamental – they are your

front line troops”. It starts with 5 days training for heads of schools, each

with one champion teacher, to

familiarise themselves with tech, then teaching with the laptop. Education must

come before technology. Then the bombshell – he pleaded for a proper academic

study on their effectiveness.

5. Vocational v academic

The Namibian

Prime Minister spoke on the first day of the conference. He was witty but also

wily. I liked him, as he warned us against the ‘spectacle of hallucination’ where technology was used to create

illusory progress. Shiny objects that dazzle but don’t deliver long-term

solutions. He urged us to focus on vocational, not academic, context and

content. Health, farming, tourism, entrepreneurship – employability was the

watchword for Africa.

Big problems need big and innovative solutions. Time and

time again I heard requests for approaches and content that are more sensitive

to context and culture. Too many projects parachuted technology and English

content that had little relevance for learners. The western idea of ’academic’

schooling was being pushed but was unsustainable. Schooling in itself is not

the answer in itself, as almost everyone in Africa leaves school – then what?

Millennium goals around schooling will not deliver unless that schooling is

relevant.

6. Health, agriculture, public sector,

entrepreneurship

I saw a myriad of useful projects around agriculture (look

out for the

www.ict4ag.org conference in

Kigali, Rwanda, later this year. Giacomo Rambaldi is passionate about the use

of technology in farming, especially around the use of m-banking (Robert Okine

in Ghana), messaging on livestock (Darlington Kahilu in Zambia), iCow in Kenya,

optimising the use of pesticides (John Gushit in Nigeria), vetinary projects –

the list goes on and on. Then the healthcare projects, nurse licence renewal,

HIV counselling (Fabrice Laurentine in Namibia), drug prescription (Lesek

Wojnowski in S Africa). I saw innovative thinking around capacity building in

the public sector. Then there’s the innovation hubs and entrepreneurship

projects. Bloggers, like Mac-Jordan Degadjor, show that the new narrative must

be created from within.

7. Sustainability

My contribution to The Big Debate focused on

‘sustainability’. You can keep on ‘taking the expensive tablets’, buy into the

myth that is Sugata Mitra’s ‘holes in walls’ or believe Negroponte’s Ethiopian

hype’ OR you can start with real problems and real, sustainable solutions.

Tech-led projects can work but only if the risks are understood and assessed

from the start. Innovation without sustainability is not innovation at all. If

you want to avoid massive failure, then watch out for tech that lies at

Gartner’s ‘Peak of inflated expectations’ as it will more than likely end up in

the ‘Trough of disillusionment’.

Africa has had a swarm of mosquito projects, what it needs

are more steady, long-lived tortoise projects. Sustainability comes in several

forms; sustainable in technical infrastructure, stakeholders, teacher training,

learner take-up, maintenance, context, relevance, languages and culture. Above

all, Africa needs sustainability in terms of costs. 20% of the poor exist on

$1 a day 20% 40% on $2 a

day. Now if the global average of ICT spend 3% of income, they can only afford

$10-$20, and it would have to be relevant. In fact they tend to spend this on

cheap mobiles. Think, then, on this. Tablets $200-$300but total costs - solar

power, maintenance & support add much, much more. These expensive tablets

have serious side-effects.

Conclusion

Monica

Weber-Fahr gave a potent presentation with a focus on social mobility. The key

point is urbanisation. This is what lifts people out of poverty. But she had a

stark warning. Social mobility is not guaranteed and by no means certain.

Africa has huge resources, huge challenges but also a huge reservoir of hope. I

came away with a different mindset about Africa. Throwing hardware at the

problems is not the solution. True solutions must be home-grown. African

projects, run by Africans for Africans, using African content relevant to

African contents and languages.

Even at the airport I was engaged in conversation with

people from Nigeria and Ghana, all eager to talk and get on with things. On the

plane I sat next to a young girl from Uganda who had been at the conference.

She was from Uganda and was brimming with hope for the future and I look

forward to seeing her next year in Kampala, where the next brilliant e-learning

Africa will take place.

PS

Well done to

Rebecca and her ICWE team for organising the conference. They were magnificent.

From the warm welcome at the airport to the final sundown party at River

Crossing, the whole experience was a joy.

Want immediate improvements in student attainment in schools,

especially in maths? Listen to this guy. He’s a pioneer. Armando Pisani is

unique. Why? He is a high school teacher who teaches 14-18 year olds in maths

and physics and is unique in that he records all of his lessons on video for later

use by students. He is also unique in that his academic background is in data

analysis, so he has gathered a great deal of useful data on his work in his

school. If his data is correct, and I think it is, he could be the catalyst for

a huge increase in productivity in schools across Europe. The following is the

result of a structured interview I did with Armando in Trieste.

Want immediate improvements in student attainment in schools,

especially in maths? Listen to this guy. He’s a pioneer. Armando Pisani is

unique. Why? He is a high school teacher who teaches 14-18 year olds in maths

and physics and is unique in that he records all of his lessons on video for later

use by students. He is also unique in that his academic background is in data

analysis, so he has gathered a great deal of useful data on his work in his

school. If his data is correct, and I think it is, he could be the catalyst for

a huge increase in productivity in schools across Europe. The following is the

result of a structured interview I did with Armando in Trieste.

+Would+you+suggest+parents+to+watch+the+online+lectures.png)

.png)